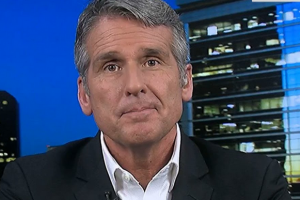

(first published June 2017)—Having been a cross-country runner in high school and college, Dan McClory knows that going the distance is the most important part of any athletic endeavor. As managing director, head of equity capital markets and head of China markets at Boustead Securities, McClory knows the same is true in international banking.

Since 2016, McClory has been working for Boustead at the firm’s El Segundo, California offices. With his fair share of high-pressure, high-powered business deals, McClory has crisscrossed the continents in his sleep, passed through multiple time-zones in a single flight, and handled multi-million dollar accounts by the time most of us are finishing breakfast—and he manages it all with the same aplomb and determination that helped him cross countless finish lines during his track-and-field days at Eastern Michigan University (EMU), Ypsilanti, MI.

Today, McClory continues to run to keep and shape (and serves on the board of the U.S. Track & Field Foundation) and to keep his relationship with God in shape while he’s at it. Among his accomplishments, McClory has led award-winning business investment teams, and he’s also helping to make investment banking more accessible on the internet and through social media by developing an online investment crowd-funding portal.

Despite the glamor and gamesmanship of international business, though, this Catholic husband and father of three children knows that a business leader is only as good as the decisions he makes and the faith he keeps—both with his clients and co-workers and in God and the teachings he imparts through his bride, the Catholic Church.

Catholic Business Journal spoke with McClory about his globetrotting business experiences, the challenges of foreign business cultures, especially in Asia, and how his Catholic faith and Catholic family life keep him grounded—even while things are up in the air—as he’s flying to Beijing or waiting for the next deal to close.

Catholic Business Journal (CBJ): How has your education background prepared you for international banking?

Dan McClory (DM): I’m originally from Detroit—I was born and raised in the Detroit area. I went to Catholic grade school—St. Francis de Sales, Detroit, and moved to a place called Royal Oak, a couple miles north of Detroit, when I entered the sixth grade. I went to St. Mary’s in Royal Oak, and then public high school and Eastern Michigan University, about 30 miles west of Detroit next to Ann Arbor, in a place called Ypsilanti. I went there to compete on the cross-country and track teams. I ran track and cross-country and served as captain of the cross-country team for three years.

I had a fantastic experience doing that with an undergraduate degree in English and a master’s degree in language and international trade. I got a quasi-business degree at that time too. In my track career at EMU, I had a fifth year of eligibility and wanted to stick around to compete. I had already graduated but it was a good way to get a master’s degree in a year.

Then immediately out of college I got a job with Ford Motor Company. I had never been west of Wisconsin and the next thing I know I’m relocating to southern California, working for Ford. I was in sales and marketing, and determined to be the next Lee Iacocca. Then I decided it would take too long—about ten years or so—and wanted to move faster. So I went into financial services and got my licenses in insurance and financial investments.

CBJ: How did you make the move to Italy?

DM: After gong into financial services, I got the equity bug to start a company of my own. Because my wife, who is Italian, was an only child, my father-in-law was trying in the worst way to figure out how to get us back to Italy and so my father-in-law pitched us on putting a company together in Italy. We started a company involved in the legal duplication of software.

The company was started in the Abruzzo region, on the eastern side of the Italian peninsula, on the Adriatic coast. It was the same latitude as Rome, two hours’ drive due east. We got cash grants, low interest loans, payroll rebates and we became one of the largest software-manufacturing firms in Europe.

I ended up selling that company to one of my competitors, and helped this other company take it public on the Italian stock exchange in Milan. Then we moved back to the U.S., around 1995, when the third of my three children were born.

CBJ: What did you do when you returned to the U.S.?

DM: In the U.S., I started investing in internet companies, during what I affectionately call the dot-comedy in the late 1990s when everything in the dot-com industry was going up in value.

I got involved in some of the companies I had invested in, and I was helping them raise capital to expand into Europe where I had a lot of connections, ultimately to go public and list their shares on stock exchanges. I figured, given what I was doing, the work of an investment banker, I ought to institutionalize myself and work for several companies simultaneously, help them raise capital and buy companies and help them list on stock exchanges. I did that in the early 2000s.

Now coming up on my second decade, I’ve been working as an investment banker, which is a form of banking where your clients are companies and you help them to raise capital to buy other companies or sell their own company. In my case, since I’m involved in the equity capital market, I’m helping them list on the stock exchange, such as NASDAQ in New York, although earlier I’ve listed companies all around the world—Hong Kong, Toronto, London, Milan, Zurich, and the Irish Stock Exchange.

My stock and trade as an investment banker has primarily been working on international transactions, as a result of my strong contacts in Europe, although in the last ten years or so I’ve been working predominantly in Asia, and particularly in China. I’ve been helping companies in China raise capital, to raise capital and doing IPOs for them on our stock exchange here in the U.S.

CBJ: How did you get involved in China?

DM: That’s what I do full time at our firm Boustead Securities. We have about 50 people in the organization focused on small and medium sized companies. We’re not typically competing with Goldman Sachs or Citibank. We do well, though, just the same. It calls for a lot of international travel. I’ve done deals in Brazil, in the Republic of Guinea in Africa, in Ukraine, certainly in China, and throughout the U.S. and Canada. It makes for quite an interesting schedule and life.

CBJ: How would you describe your work as “Head of China” for Boustead’s?

DM: Mainly I meet with companies in China that want to raise capital and money to grow. They want to do that by listing their company on the stock exchange. We meet with these companies, conduct analysis and due diligence. We make sure they’re acceptable, get them audited and put the right legal structures in place. Then we file with the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) to have their securities registered so they can trade on a stock exchange. I have money for sale, I guess you could say, and I meet with these Chinese companies to decide which ones the money should go to.

It’s not my money but the money of investors who put money into deals we get behind. We underwrite their initial public offer (IPO) and we work as wholesale bankers who bring capital to companies that want to take on outside investors so they can grow, more so than if they simply reinvest their profits every year.

CBJ: How has your family background formed who you are personally and professionally?

DM: I’ve been married 34 years in August. My wife and I have three children, a son, 29, another son, 26, and a daughter 23. My oldest son is following in my footsteps a little bit. He’s completely fluent in Mandarin; he’s a 6-foot 2-inch white guy who can read, write, speak, bank and remember everything in Mandarin. He works for a Chinese investment bank in San Francisco.

Both of my uncles are priests with the order of Precious Blood; one is deceased and one is still alive. One was a missionary in Chile for 13 years during the Pinochet revolution and oppression, and the other won $440,000 on a slot machine on a Mississippi River boat casino. He said the hardest thing was giving all that money to the IRS because they take all that money out for taxes right there at the casino.

He got onto the Jay Leno show for it; It’s not typical that a Catholic priest wins almost half a million dollars on a quarter slot machine.

My mother Ann just died last October (2018). She had a great life. She was studying to be a nun and right before she took her final vows she decided she had a calling to raise a family and left the convent. In five years, she had four children—two brothers, a sister, and myself. She met my father, James, who is still alive and 94 years old. They met seven decades ago as lay members of the Third Order of St. Francis in Detroit. They met while they were in a bowling league together. They were married just under 60 years when she passed away last October.

CBJ: You also have a brother who is a priest (now archbishop)?

DM: My younger brother, Robert is also a priest—Archbishop Robert J. McClory (ordained bishop in 2019) . He’s an interesting guy. He got his degree in political science at Oakland University, and then went to Columbia and got a master’s in public administration, and then went to the University of Michigan law school and became an attorney.

He practiced law for about four or five years, decided he had a calling to be a priest, showed up at the Sacred Heart Seminary in Detroit and then was sent to the Pontifical North American College (NAC) in Rome. The NAC is considered the Harvard or West Point of seminaries for U.S. priests.

That was in 1995-1996, and when my brother was at the NAC, the NAC’s rector was Timothy Dolan, who is now the Cardinal of New York. Bob’s graduating class had Antony Scalia’s son in it, and the son of John Ricardo, the chairman of Chrysler. In Bob’s class, a journalist, Brian Murphy, was embedded who wrote The New Men: Inside the Vatican’s Elite School for American Priests. More recently, Bob was in Rome when the University of Michigan football team was there and he met U of M’s coach Jim Harbaugh.

CBJ: What was the learning curve for international finance?

DM: I would say it’s like anything that ends up being commission- or results-based. The challenge is to establish yourself quickly enough so you don’t go bankrupt getting into the business.

It was also a challenge developing some form of a track record of successes that I could point to. People don’t always want to know about your last or your best deal but only about your last worst deal.

As Winston Churchill said about politics, the definition of success is moving rapidly from one failure to the next. So there’s also a challenge in being able to keep going and moving despite the challenges and hurdles. Some of that sounds cliché but it’s true. People remember you when things go wrong but not when the fish are jumping in the boat.

On the other hand, there’s a value to these challenges. When things go sideways I want to know how someone is going to act in a given situation.

CBJ: How did you get involved with FlashFunders.com?

DM: That is a crowd-funding portal. Crowd-funding is a new way under SEC regulations to raise capital by essentially using social media to inform investors about deals. Since Boustead bought FlashFunders recently, in addition to marketing our deals in the old fashioned way on the phone or in person or even by sending emails and scheduling meetings, we also put them online and list them at FlashFunders.com.

We only have three deals up there right now but are in the process of moving other deals to the site. It’s a new way to market deals to investors that is faster, less expensive and greatly enhanced because you don’t have so many prohibitions on marketing.

When you’re marketing an ISO through conventional means, you can only market it to those who are accredited. But with crowd-funding, you can market more generally and in a widespread way using the internet as long as you follow certain procedures and regulations. FlashFunders is the wave of the future and there are many other crowd-funding portals out there.

But FlashFunders is about to have completed the first ever crowd-funding IPO that will trade on NASDAQ. That deal will be between $15-20 million in capital.

Many typical crowd-funding deals are for $50,000, $500,000 or $1 million.

Crowd-funding also democratizes the capital-raising process. It gives smaller companies more ways of reaching out to investors instead of through the old school or old boy networks.

CBJ: How do you bring your faith to work, particularly your work in China, where the government is officially atheist?

DM: The scruples and business ethics and definitions of what’s right and wrong and acceptable are somewhat different in China. It could be OK, for instance, (and these claims don’t apply to all Chinese business leaders) to misrepresent something, to lie or overstate something, or agree and change your mind on something after the fact. I look at that as an occupational rather than a moral hazard. Going into transactions, I know already that things are probably going to change before everything is said and done. In fact, there’s a saying that in China that agreements are a pause between negotiations.

More specifically, if we see moral hazards in a deal, we wouldn’t engage it, for a variety of reasons, considering such perspectives as faith, and religious and ethical values, and even because of liability.

CBJ: How do you find the religion being treated in China?

DM: It’s been said that there are going to be 50 million Catholics in China by 2020. That’s out of 1.2 billion people, but still, that’s remarkable.

One of China’s emperors, the Wanli Emperor Zhu Yijun (1563-1620) was classically trained by a Jesuit named Matteo Ricci in the 1500s. Father Matteo taught the emperor science, math, and a little philosophy. The priest learned Mandarin, and he’s revered in China. There’s a monument to Father Mateo in Beijing, near his gravesite, at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, which is part of the authentic Catholic Church, not the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Church established by the government [but not recognized by the Catholic Church as legitimate]. To find that out about China gave me a new understanding of the country’s history and indebtedness to the Church.

CBJ: What was your faith journey growing up? How did you embrace the faith as your own?

DM: From a very young age, I had experienced an extremely religious and observant Catholic life and household—everything from going to school to receiving the sacraments, along with the reinforcement of my priest uncles, who were fun guys.

In college, in the early years of my career, I would say I wasn’t as intense in my faith and I would go not so often to Mass. But I survived, thanks to my family; there was constant encouragement from my family to keep the faith.

I’m 57 now, but in the last 12-15 years I’ve come to see that my Catholic faith is something special and important to me. I’m extremely blessed to have my faith. All my children were raised Catholic in Italy. I’m aware of the strength and power of the faith and what it can do not just for me, but also for my family and even people I don’t know and come across on the street.

CBJ: How has your faith helped you in your professional life?

DM: In general, my attitude toward running my affairs, professional or personal, has been affected by my faith. Taking that direction is so much more fulfilling, so much more satisfying than other approaches in business, which are more “me-first.”

Every day I thank God for three things: his mercy for the past, his love for the present, and his providence for the future. Understanding and knowing and believing that God is active in my life is reflected in my relationship with my family, my professional relationships, and increasingly in charitable and philanthropic causes I’ve become involved in.

All this has been greatly reinforced in me in the last decade not because of a singular life-changing experience but because God is responsible for everything we are, say, do and have. We’re here temporarily and should strive to be the best possible stewards of all we have. As much as I force it and make it about me, I know it’s not.

As my parents always told me growing up, virtually every day, I and my brothers and sisters are gifts from God. It’s absolutely the case. I feel that way about my own children. Everything we have, we’ve been blessed to have.

Life is not without interruptions and speed bumps and challenges, but there’s a bigger purpose for being here and a much bigger person overlooking all this and making sure it all works out right.

CBJ: How do you fit prayer into your busy globetrotting life?

DM: My sister eight years ago got me turned on to Magnificat. She gave me the latest issue and urged me to subscribe to the publication. She had the courage to point out the wonders of Magnificat to me.

So now I read it in the morning and then I go out and do a run for two or three miles. When I used to go on my run, I would solve all the problems of the world: how I would make money, what I was going to do that day, which items on my to-do list I was going to check off my list that day.

But for the last couple years, I’ve turned that time exclusively into prayer time. I have a whole routine which runs about 30 minutes—all the prayers I say for that day, between 5-6 a.m., usually in the dark, in the cool of the morning, as cool as it gets in California, anyway.

Then I’ll usually without fail go through an entire office of sorts in prayer. Prayer is a great start for the day as opposed to prioritizing which deal I was going to close or being concerned about a particular situation. I push that stuff aside and start the day with a good solid half hour of focused prayer.

Run with It!

How do you make time in your busy professional life for God? How has your career been guided by God’s providence and how has God communicated that guidance—and his will for you—in your life? Do you find inspiration in Dan McClory’s story of perseverance in the face of a steep cultural learning curve? Feel free to let us know in the Comments section or on our FaceBook page.

RELATED RESOURCES:

Dan McClory: Head of China Equity Investments talks with Host Ric Brutocao about his career and doing business in China —The Mentors Radio Show (podcast available, free, details at TheMentorsRadio.com)

————————

Joseph O’Brien is a Catholic Business Journal correspondent. He may be reached at jobrien@catholicbusinessjournal.biz, or email c/o admin@catholicbusinessjourhal.biz. Interview originally ran 6/7/17. Copyright CBJ LLC.

You must be logged in to post a comment.