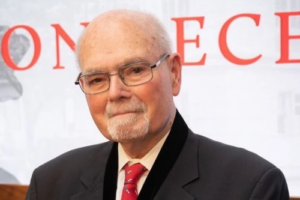

CNA—Author and Catholic convert Lee Edwards, one of the foremost historians of the conservative movement in America, died Thursday. He was 92.

Edwards co-founded the Victims of Communism Memorial in Washington, D.C., authorized by Congress in 1993 and completed in 2007.

He was a distinguished fellow of conservative thought at the Heritage Foundation for about 25 years before retiring about a year ago.

He also wrote 25 books. Among them are well-known histories of American conservatives and conservatism — and lesser-known works, including “John Paul II in Our Nation’s Capital,” the Archdiocese of Washington’s official account of the pope’s visit in October 1979.

“He was an optimist, very much upbeat. He believed God had a plan for each of us,” his daughter, author and political scientist Elizabeth Spalding, told CNA.

Anti-communism

The turning point in his life’s work came in 1956 when he was taking graduate classes at the Sorbonne in Paris when Hungarians, including students about his age, briefly overthrew the communist government there.

“And for those almost two weeks, my dad thought, ‘This is it. This is it. We’re going to beat communism,’” Spalding told CNA.

Then the Soviet Red Army invaded Hungary, crushed the revolt, and restored communist rule. The United States and its Western allies did nothing.

“My father said, ‘Right then, I swore I would spend the rest of my life trying to defeat communism and help those fighting for their freedom,’” Spalding said.

Edwards helped found Young Americans for Freedom in 1960 and edited its magazine, New Guard. He later served as an aide to the Republican presidential nominee in 1964, U.S. Sen. Barry Goldwater.

In 1967, Edwards wrote a political biography of Ronald Reagan during his first term as governor of California, through which he got to spend time with Reagan and his wife Nancy. Edwards became familiar with a code term Reagan used with some of his aides — “the D.P.,” which meant “the Divine Plan.”

Edwards updated the book after Reagan became president. It came out not long after Reagan was shot and seriously wounded in March 1981. For that edition, the publisher put a yellow border on the cover saying it was “complete through the assassination attempt,” which mortified Edwards.

Still, Edwards got to meet Reagan in the Oval Office, and he presented Reagan with the updated version of the book.

“President Reagan puts down the book,” Spalding told CNA, “and then looks over at Dad and says ‘Well, Lee, I’m sorry I messed up your ending.’”

Man of Freedom

Freedom and conservatism were at the center of Edwards’ outlook.

“Mine has been a life in pursuit of liberty,” he wrote in his 2017 autobiography “Just Right.”

Edwards wrote biographies of Reagan, Goldwater, Edwin Meese, and William F. Buckley Jr. as well as books about conservatism.

In his 50s, Edwards earned a doctorate in political science from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., with a dissertation on the origins of the Cold War. He later taught there as an adjunct professor.

In 2017, he told an interviewer that he was about to teach a course on the 1960s, during which he planned to present what he called “both sides of the picture” — meaning not just the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam movement, which students often hear about, but also what he referred to as “the rise of the right” — including Goldwater and Reagan.

Conversion

Edwards was born Dec. 1, 1932, in Chicago but grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland.

He was raised a Methodist. His father, a political reporter for the Chicago Tribune, was a lapsed Catholic, though he later returned to the Church.

In college Edwards stopped going to services because he realized he didn’t believe in the resurrection of Jesus.

But in his mid-20s, he decided he needed religion to center his life, he said, after spending a mostly fruitless time in Paris drinking too much beer and chasing too many girls.

“For the first time in my life, I admitted that I needed someone, something, other than myself to give purpose and meaning to my life: in short, I needed God,” he wrote in an article in Crisis Magazine in January 1994.

When he got home he tried several Protestant churches. Then one day he went to Mass at St. Peter’s on Capitol Hill.

“I said, ‘Oh, this is something different,’” he told The Arlington Catholic Herald for a December 2017 profile.

A Redemptorist priest at the Catholic Information Center in Washington, D.C., gave him religious instruction and eventually started getting on him to join the Church. Edwards hesitated, coming up with various objections and uncertainties before finally agreeing.

The delay led to an unusual date to become a Catholic — not Easter time, which is the most common time to enter the Church, but Saturday, Dec. 13, 1958 — St. Lucy’s feast day. Yesterday was the 66th anniversary of his being received into the Church.

Edwards later wrote that when he knelt at the Communion rail to receive Communion for the first time, next to him on one side “was a young Black boy in his dark blue Sunday suit and on the other an elderly white woman in a worn cloth coat and hat.”

“Dad always said part of what he loved was the universality of the Catholic Church,” Spalding told CNA. “Everyone goes up to Jesus.”

Our Lady

While he was working at the Heritage Foundation he was a common sight at the midday Mass at St. Joseph’s Church on Capitol Hill.

Spalding told CNA that many people have contacted her during the past day or two to say they felt inspired by how he witnessed to his faith.

“It’s something he didn’t talk about all the time,” she said. “It’s something he lived.”

Edwards was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in June. As he neared the end, his daughter said, she and her father discussed what his death day might be.

Edwards died a little before 8 a.m. Thursday, Dec. 12, the feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

That shouldn’t have surprised the family, his daughter said. To try to keep warm during his declining days, he used a polyester lap blanket with a mostly black background and a colorful image of — Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Edwards’ wife of 57 years, Anne, who assisted him in all of his writings, died in November 2022. Their gravestone, designed by the sculptor of the statue in the Victims of Communism Memorial, features an image of St. John Paul II holding a crozier and the words “Be not afraid.”

He leaves behind two daughters and 11 grandchildren.

A funeral Mass is set for 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, Dec. 19, at St. Rita Catholic Church in Alexandria, Virginia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.