Column: CEO Learnings

Tom Perkins, the co-founder of the legendary venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins, was a towering figure in the world of venture capital and entrepreneurship. I had the distinct privilege of learning directly from him.

Perkins’ influence on my journey

Tom’s influence on my professional journey is profound and enduring. The lessons I gleaned from our interactions and observations of his approach have provided a blueprint that has shaped my thinking and guided my decisions for more than four decades.

These insights have been instrumental in fostering innovation and in developing young, groundbreaking companies to address unmet needs in healthcare. Over the course of my career, I have been involved in commercializing more than 20 medical products in 13 diverse medical domains.

How we met

Before working with Tom, I spent 13 years at American Hospital Supply Corporation (AHSC, now Baxter). As a turnaround specialist, I gained invaluable and extensive experience in both  product management and operations across 13 U.S. and international divisions.

product management and operations across 13 U.S. and international divisions.

In my final five years, I served as President of AHSC’s Heyer-Schulte Subsidiary, a company specializing in Class III medical implants. Under my leadership, Heyer-Schulte achieved an NEBT return of 42%.

Then Tom recruited me from AHSC to transform Kleiner Perkins’ first medtech investment, Novacor, from a research organization into a fully operational company.

At the time, Novacor, a Class III medical device company, was pioneering the development of a left-ventricular heart pump. This opportunity opened doors to what would become for me more than four decades of work with development-stage companies in medical technology, connected health, and more recently, in biotherapeutics.

From Tech Leader to Venture Capitalist

Before becoming a venture capitalist, Tom had a distinguished career in the tech industry, where he oversaw product development, manufacturing and marketing.

In 1963, Bill Hewlett and David Packard invited him to become the administrative head of Hewlett-Packard’s (HP) research department. As the first general manager of HP’s computer division, Tom played a pivotal role in ushering HP into the mini-computer business.

During the 1960s, Perkins also co-founded University Laboratories, which later merged into Spectra-Physics, where he co-developed the first low-cost, He-Ne laser by ingeniously integrating the laser cavity mirrors inside the plasma tube.

His ability to recognize and create value

Tom’s hands-on operational experience and deep understanding of how various company functions integrate to create value were evident not only in my interactions with him but also in his role as Novacor’s Chairman of the Board.

Tom had unique and practical insights on creating value, as he had done it himself. He also understood the intense pressures of entrepreneurship, knowing exactly what was needed  when things got heated, making him an invaluable mentor and leader.

when things got heated, making him an invaluable mentor and leader.

Working with Tom and other pioneering venture board members—Gene Kleiner, co-founder of Kleiner Perkins; Reid Dennis, founder of Institutional Ventures; and Moshe Alafi—was like earning an MBA in venture investment and company building.

KEY LEARNINGS from Tom Perkins

Key learnings I gained from Tom that enabled my transformation from a corporate executive to a development stage entrepreneur include the following.

1. The CEO is the Captain of the Cheerleaders

When I joined, Tom told me that he and the board served as our cheerleaders. However, I quickly learned this was true only when things were going well. The CEO is the chief  cheerleader. The CEO must keep the team, board and investors positive and enthusiastic. No one else can fill this role. If done well, others will join as members of the cheerleading squad, but only the CEO can serve as the captain.

cheerleader. The CEO must keep the team, board and investors positive and enthusiastic. No one else can fill this role. If done well, others will join as members of the cheerleading squad, but only the CEO can serve as the captain.

2. Maintain a Relentless Focus on Value Creation

One of the most profound impacts Tom had on me was his unwavering discipline to focus on value creation.

With his deep knowledge of markets and technology, coupled with his operational understanding of how things get done, Tom was adept at creating value roadmaps.

He identified or helped teams not only identify key development milestones but also how they build on one another to create the best path to value for all stakeholders. He ensured capital infusions were based on what was learned at each milestone.

If results met or exceeded expectations and the risk of failure was reduced, more capital would flow into the company, enough to reach the next milestone.

This laser focus ensured that every action and decision was geared towards building and enhancing value, a principle that I have since adopted and applied throughout my career.

3. Invest Time and Money Solely in Transformative Solutions for Big Unsolved Problems

Tom was focused on solving big problems because they created great value. Even if the effort fell short, it could still result in a viable, albeit smaller, company.

In contrast, solving small problems offered little retained value if they failed. Tom was unafraid of failure; he embraced uncertainty and the risks that came with it. He didn’t rely on 15-year proforma statements for decisions.

Tom understood that development was relational, not linear.

Having experienced the cycle, Tom Perkins knew that no plan would last a year as new learnings would emerge once development began. Success depended on integrating these learnings quickly into the development plan and knowing when to quit.

4. Tom Perkins’ Key Questions

When people pitched investments to Tom, he focused on key questions:

- What is the problem to be solved?

- How big is the problem?

- What is the transformative technology to be employed?

- How strong is intellectual property?

- Who is leading the team? Who else comprises the team?

- How much capital is needed to reach the first high-value milestone?

- Lastly, he wanted to know how much capital was needed to reach the first high-value milestone.

Tom had an unparalleled ability to identify promising entrepreneurs who could connect the dots between transformative technologies and large unserved needs in society. As a co-founder of Kleiner Perkins, he was instrumental in funding many notable entrepreneurs and their companies over the past 40 years, including Jeff Bezos, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Jim Clark, Vinod Khosla, Scott Cook and Eric Schmidt.

These investments not only highlight Perkins’ vision but also his ability to identify and support transformative technologies and the entrepreneurs behind them.

Perkins’ Investment Philosophy

His investment philosophy was straightforward: find great people with big ideas, provide needed risk capital and organizational support, and then get out of the way.

His visionary investing taught me to look beyond conventional wisdom and the immediate horizon and to trust in the potential of groundbreaking ideas and great teams.

The Board and Its Composition Matters

Over my four decades of working with development-stage companies, I have collaborated with a diverse group of venture investors and board members.

Tom set the gold standard for me.

He had the complete package: product development, operating experience and big company expertise.

In short, Tom Perkins knew how things worked in a company, how to get things done, how to develop technologies, and how challenging it is to transform an idea into a viable product.

He was intrigued by new innovations and was a quick learner. Tom knew how to roll up his sleeves, solve problems and navigate the pressures of being an entrepreneur, having experienced it firsthand.

What makes an effective board?

From Tom, I quickly learned the importance of an effective board.

Effective boards are not made up of family and friends but rather of experienced professionals with domain-related research and development experience, start-up operating experience, scaling, market, and global experience. They have tasted failure but have not let it deter them from taking meaningful risks.

Understanding cash flow management is also crucial; income statement management comes later in the game with revenues. The attributes needed in board members are not static and evolve as the company matures.

Critical importance of a well-chosen lawyer

A seasoned lawyer with extensive experience with development-stage companies is critical for the role of corporate secretary. While they may seem expensive, they can be invaluable and cost-effective with their networks, deal-making experience, and knowledge of the ecosystem regarding the specifics of deals getting done, who is investing and deal terms. You need a corporate secretary who knows what they’re doing, not someone who is learning on your dime.

Tom exemplified the critical value of a board member with operating experience. Having served as general manager at HP, Tom, like most effective general managers, knew who and what to trust.

Understand—really understand, hands-on—How things get done in the trenches

He understood how things get done in the trenches and was humble enough to acknowledge that he did not know everything. As such, he was a good listener and asked insightful questions.

Being responsive, treat all with dignity

He was responsive, promptly returning phone calls, and treated everyone with dignity, thereby earning the respect of both the board members and the executive team.

When I came to Novacor, I came from an environment where I reported to someone whose interests lay solely in innovation and research, with little focus on marketing and manufacturing. Our meetings revolved more around product development than actual business strategy.

How Working for Perkins was different

Like Tom, I had product development and general management experience in aerospace and medtech. I vividly remember sitting with Tom, discussing strategy and the next steps for our company’s development.

Tom had an uncanny ability to finish my sentences, a testament to his comprehensive grasp of the business.

His strategic guidance was not just theoretical; it was grounded in real-world experience and a clear vision of how different functions needed to integrate for success. This holistic understanding of business operations reinforced the importance of a well-rounded approach to leadership and company building.

I have seen many boards of development-stage companies that lack operating or R&D experience. Yet board members with this expertise are a “must-have” for oversight and are especially crucial when dealing with setbacks.

Unfortunately, many individuals seek board positions without being a good fit, often adding chaos due to their lack of relevant experience, despite the capital they represent.

Deep-dive Due diligence

I learned the necessity of conducting due diligence to ensure the right individuals would represent an investing fund.

Occasionally, investors want to add one of their partners or junior partners as observers. Avoid them. Over time, they may act as board members without having a fiduciary role, leading to problems. A well-composed board is a strategic asset.

Focus Board Meetings on Strategic Decisions, Not Holiday Gifts

When I entered the venture-funded business-building world, I heard many stories of start-up board meetings lasting hours, sometimes all day.

I attended a board meeting where the first two hours were spent discussing holiday turkeys for employees. This was not the case with Tom.

With Tom, our board meetings lasted no more than three hours, with everyone expected to have read the board materials provided a day before. Tom ran a tight meeting, always focusing on the critical strategic issues.

Tom avoided routine updates during the meeting, as those could be included in the pre-meeting materials. Instead, he directed everyone’s attention to key issues and finding solutions. Meetings under Tom’s leadership were efficient and solutions-oriented. This experience has shaped my approach for 40 years.

I was always amazed by Tom’s ability to stay on top of the pulse and issues, even while serving on the boards of 15 companies. His focus was remarkable. I have only seen this level of focus in one other board member since, Dave Chonette, who was at Brentwood and then co-founded Versant Ventures.

Find Investors Who are Company Builders

Tom taught me that while many in the venture capital ecosystem claim to understand what it takes to build companies from scratch and create value, not all of them truly do. Building pioneering, transformational technologies to solve big problems has no set formula. As the first to venture into new territories, the entrepreneur is essentially creating the “cookbook.” Setbacks and failures are integral parts of the creation process. There are always unseen obstacles, detours, roadblocks, and new learnings. The development process, as stated earlier, is relational, not linear. Information and knowledge gained must be embraced and integrated into the team’s thinking.

Gene Kleiner famously told me, “All great startup companies were at death’s door at some time.” A key success attribute of a team (and its investors and board members) is how they respond to unforeseen challenges. Embracing and overcoming these challenges strengthens the team and board.

Those who lack experience and sophistication are often rattled by these challenges and act less like company builders and more like banks. Their behavior can become problematic, slowing progress and creating internal strife. In contrast, experienced and sophisticated investors actively embrace these challenges as part of the process and move on. Fortunately, Novacor set a gold standard for me. They had a seasoned, sophisticated startup board that navigated these challenges effectively.

If the Executive Team Does Well, We Do Well

Perkins was empathetic to the executive team. He understood the challenges, the hard work required, and the risks of a startup, having experienced them himself. He recognized the immense value of the team in executing a plan amid great uncertainty and ensured they were properly incentivized to succeed.

He often asked, “How well is the executive team compensated (with substantial stock options)?” His standard refrain was, “We need to take good care of them. If they do well, we do well.”

Unfortunately, this approach has been abandoned by many venture investors over the past 20 years. I have seen executive teams being nickel-and-dimed by boards and investors trying to squeeze as much upside as possible from the team’s compensation to enhance their returns. Many have lost sight of the crucial role that performance-aligned incentives play in achieving success. It is paradoxical, as those leading startups—and their families—sacrifice a lot for the investors. I often think back to Tom and his philosophy of compensation. He was right.

Shake the Dust Off and Get Out of the Office; Money Does Not Grow on Trees

The CEO of Novacor was a scientist who believed it was the board’s primary responsibility to raise money for the company. This frustrated Tom immensely. In one of my first one-on-one meetings with Tom, he complained about the CEO’s passive attitude toward raising capital. Perkins and the other board members were involved in multiple companies. They provided the initial capital and invested pro-rata as risks were reduced, but they did not consider it their duty to find new investors. They could make introductions, but it was up to the company to pitch and engage new investors.

This was a crucial lesson for me, as many entrepreneurs shared my CEO’s mindset.

I learned that securing funding is one of the CEO’s primary activities and must be approached proactively. It cannot be delegated to anyone else. No matter how difficult the environment, securing funding is a primary responsibility of the CEO.

Quit to Get Ahead

Tom had plenty of grit but also knew when to quit. Novacor’s CEO, a scientist, faced transparency issues, and the board, including Perkins, wasn’t fully informed about some technical risks and capital allocation. We had two versions of the pump: one designed for an NIH grant and another for the commercial market, designed for patients. Contrary to the board’s understanding, venture capital was being used for both pumps, hoping NIH funding would benefit the commercial pump. Value creation was vested in the commercial pump.

When I joined Novacor, Medtech IPOs were drying up due to new TEFRA regulations, making it impossible to raise money for Class III medical implants. The pump also had serious technical issues, which, in addition to the misallocation of capital, I reported to the board. This mix of problems led Tom, with the board’s agreement, to decide to shut down Novacor.

Novacor, due to its complexity and financial needs, was not a fit for where the venture capital industry was at that time in its evolution.

With only two weeks to shut down, I threw a Hail Mary pass and managed to secure significant financing from an unlikely source, American Medical International, a for-profit hospital management company. With new capital, Tom and I agreed to shrink the company and eliminate spending related to commercialization. I estimated it would take ten years and another $130 million to reach commercialization. I eliminated my job, and we sold Novacor to Baxter, which spent $150 million and took ten years to sell the first pump.

Tom and I moved on separately to new opportunities. I joined a transformational eye care company in the emerging field of refractive surgery and was able to bring Kleiner Perkins, through Tom, into the deal. Quitting Novacor allowed us to find success elsewhere. Quitting is not a bad thing, as I learned. Everyone, including Novacor, ultimately benefited.

Enrich Your Life by Increasing Your Understanding and Pursuing Transforming Experiences

Despite his busy schedule, Tom had a rich array of outside interests. His wife, Gerd, a significant influence in his life, introduced him to the performing arts. Shortly after I joined Novacor, I learned that Tom played a pivotal role on the Board of Trustees for the San Francisco Ballet Company. During a turbulent period with its Artistic Director, Tom persuaded the Board to fire the problematic director and led the search committee for a new Artistic Director. He successfully recruited Helgi Tomasson, who transformed the San Francisco Ballet into one of the world’s preeminent companies and developed an internationally acclaimed school. Tom’s influence extended to me, and I became an annual subscriber to the San Francisco Ballet for over 20 years, trusting that anything Tom was involved in would hold value. It did.

I was also impressed by Tom’s reading habits.

On a flight to Southern California to meet with key executives at American Medical International, I noticed him reading Paul Tillich’s “The Courage to Be.” This choice of literature  highlighted that there was much more to Tom than his role as a venture capitalist.

highlighted that there was much more to Tom than his role as a venture capitalist.

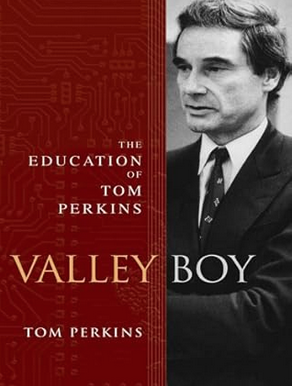

Tom was also a passionate and knowledgeable sailor. He envisioned and built the groundbreaking 88m sailing yacht, the Maltese Falcon, equipped with three free-standing carbon fiber masts and 15 square sails that could be set at the press of a button. The yacht also featured remarkable modern art, making it a transformative addition to the sailing world. Perkins detailed this journey in his book, “Valley Boy: The Education of Tom Perkins.” For insights into Tom’s thinking and approach in the venture field, the section on creating the Maltese Falcon is both instructive and entertaining.

Conclusion

Reflecting on my experiences with Tom, I realize that his ten lessons extended far beyond the boardroom. His relentless focus on value creation, his strategic insight, and his ability to navigate complex challenges have profoundly shaped my approach to business. Tom’s commitment to fostering innovation and his understanding of the human element in entrepreneurship have left an indelible mark on me and countless others. He demonstrated that building great companies requires more than just capital; it demands great people, vision, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to solving big problems. As I continue to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of venture capital and entrepreneurship, I carry with me the invaluable wisdom and principles imparted by Tom, a true legend in the field.

This is the second in a series of “What I learned from…” stories of my key mentors.. My first article which features American Hospital Supply’s Bill Bartlett can be found at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-i-learned-from-bill-bartlett-thomas-m-loarie-vqopc/?trackingId=lFCC0Ln2Sim4KyOBgVRVYA%3D%3D

RELATED RESOURCES:

- The Courage to Be, by Paul Tillich

- Valley Boy: The Education of Tom Perkins, by Tom Perkins

View Articles Thomas M. Loarie is a popular host of The Mentors Radio Show, the founder and CEO of BryoLogyx Inc. (BryoLogyx.com), and a seasoned corporate... MORE »

You must be logged in to post a comment.